- Home

- Diego Rivera

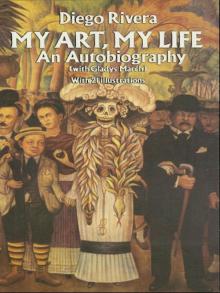

My Art, My Life

My Art, My Life Read online

IN GRATITUDE

to DIEGO

whose dynamic companionship was an illumination in my youth;

and to ALFRED

my patient, dearly beloved husband, who helped to sustain and enrich its radiance

—G. M.

This Dover edition, first published in 1991, is an unabridged republication of the edition originally published by The Citadel Press, New York, in 1960. The entire text has been typographically reset with corrections and with many Spanish accents added. The list of illustrations is a new feature of the present edition.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rivera, Diego, 1886–1957.

My art, my life: an autobiography / Diego Rivera with Gladys March.

p. cm.

Reprint. Originally published: New York: Citadel Press, 1960.

Includes index.

9780486139098

1. Rivera, Diego, 1886–1957. 2. Painters—Mexico—Biography. I. Title.

ND259.R5A2 1991

759.972—dc20

[B]

91-22815

CIP

Table of Contents

Title Page

IN GRATITUDE

Copyright Page

Foreword

GEOGRAPHICAL, GENEALOGICAL

TALE OF A GOAT AND A MOUSE

THE THREE OLD GENTLEMEN WELCOME THE NEW ICONOCLAST

MY THREE AMBITIONS

I BEGIN TO DRAW

WE MOVE TO MEXICO CITY

SCHOOLS

MY FIRST EXPERIENCE OF LOVE

THE BEGINNING AND END OF A MILITARY CAREER

AT THE SAN CARLOS SCHOOL OF FINE ARTS

THREE EARLY MASTERS

POSADA

PRE-CONQUEST ART

AN EXPERIMENT IN CANNIBALISM

MY FIRST GRANT

MURILLO ATL

PASSAGE OF ANGER

MY SPANISH FRIENDS

DESOLATE LANDSCAPES

CHECKBOOKS IN MY FINGERS

ART STUDENT IN PARIS

PRIVATE PROPERTY

NO MORE CÉZANNES

THE SUN WORSHIPPERS OF BRUGES

BEGGARS IN TOP HATS

A QUALIFIED SUCCESS

WHERE I WAS IN 1910

HOMECOMING!

A WITCHCRAFT CURE

REVOLUTIONARY WITH A PAINTBOX

A PLOT TO KILL DIAZ

DEHESA

SEA DUTY

REUNION WITH ANGELINE

PICASSO

WAR

YOUR PAINTING IS LIKE THE OTHERS’!

MARIEVNA

AN END AND A BEGINNING

IN ITALY

I AM REBORN: 1921

LUPE

AN APPARITION OF FRIDA

THE MEXICAN RENAISSANCE

THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND CHAPINGO

HITLER

STALIN

MOSCOW SKETCHES

AN INSPIRATION

H. P.

THE ASSASSINATION OF JULIO MELLA

I AM EXPELLED FROM THE PARTY

CUERNAVACA

FRIDA BECOMES MY WIFE

A BID TO PAINT IN THE SAN FRANCISCO STOCK EXCHANGE

ONE-MAN SHOW IN THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

A VISIT WITH HENRY FORD

THE BATTLE OF DETROIT

FRIDA’S TRAGEDY

HOLOCAUST IN ROCKEFELLER CENTER

RECONSTRUCTION

THE NAZIS LEARN HOW TO DEAL WITH ME

PANI LOSES AN EYE

AN INVITATION FROM MUSSOLINI

FRIDA: TRIUMPH AND ANGUISH

TROTSKY

THE ENORMOUS NECKTIE

A VISIT WITH CHARLIE CHAPLIN

A SALUTE BY THE U. S. NAVY

TROTSKY AGAIN––DEAD

A SECOND TIME WITH FRIDA

MORE POPULAR THAN WENDELL WILLKIE

PIN-UPS, SALOON STYLE

A HOME FOR MY IDOLS

A SUNDAY IN ALAMEDA PARK

CARDINAL DOUGHERTY DEFENDS

AFTERMATHS

UNDERWATER

ANOTHER STORM

CANCER

YET ANOTHER STORM

FRIDA DIES

EMMA—I AM HERE STILL

APPENDIX

INDEX

A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST

DOVER BOOKS ON ART, ART HISTORY

Foreword

GENETICALLY, THIS BOOK BEGAN as a newspaper interview which Rivera granted me in the spring of 1944. But it did not begin to assume the proportions of a book—even in my mind—until the following year, when we first discussed my writing it. I spent six months with Rivera in 1945, working hard at what he would call “the preliminary sketch.” In the years that followed, usually summers, I would go down to Mexico for a month or two to review and supplement my notes and to find out what “news” had occurred since my previous visit. Diego Rivera’s was an active and many-sided personality: his mind was quick, his imagination staggering; so there was always much to be added. The interviews which began in 1944 ended in 1957 because my notes, now bulking over two thousand pages, suggested that I might now have all I needed.

From the outset, Rivera framed much of his dialogue in the form of short personal narratives, and these narratives compose the skeleton as well as much of the meat of this book. But a good deal of his talk, too, consisted of anecdotes, unguarded remarks, and opinions on art, people, and politics, which I later interpolated in their proper places in the story.

Fortunately for me, Rivera seemed to be flattered by the continual attentions of a young American woman. I literally walked in his shadow, and he let me go with him everywhere as he spun his tales. Most of our dictating sessions took place while Rivera was engaged in painting, at his studio. But conversations ran over into mealtimes, and I made notes in his car en route to lectures or parties, in his home, and on walks. I met his wives, his daughters, his friends—many of the people who appear in this book.

In collating my notes, I found that much that Rivera had said orally could stand up as writing, or could not be changed without some loss, call it the flavor of his personality. Of course, nobody’s dialogue is consistently good, but wherever I pared phrases, unwound sentences, or lopped off tautologies and digressions, I endeavored to remain faithful to Rivera’s style. Essentially, this is Rivera’s own story, told in his words. As such, it may not always coincide with what other people might call “the facts.” Élie Faure was one of the first to recognize a dominant quality of the artist’s mind: “Mythologer, I said to myself, perhaps even mythomaniac!”

Rivera, who was afterwards, in his work, to transform the history of Mexico into one of the great myths of our century, could not, in recalling his own life to me, suppress his colossal fancy. He had already converted certain events, particularly of his early years, into legends. Both Bertram D. Wolfe and Ernestine Evans, who wrote books about him, grappled with this problem. And the reader will react to it according to his purposes as he encounters it here. My task, however, was to be neither judge nor censor. An autobiography must encompass the whole man: what he has made of the facts, as well as the facts themselves.

In addition to recording and organizing Rivera’s dictation, and making grammatical and literary changes in the text, I added—always with his approval—material from previously published books, articles, and interviews to fill in such gaps as inevitably appeared. For this reason, however, no claim can be laid to completeness or definitiveness. There were aspects of his life which Rivera did not care to recall, and as his amanuensis, I could only respect his reticence.

The artist’s a

ccount of his relations with Leon Trotsky, for instance, all but conceals a genuine attraction he felt toward Trotsky’s Fourth International. But when I met Rivera, in 1944, he was seeking readmittance into the Communist Party. For this reason, also, his description of his journey to Russia in 1927 omits much that he had earlier confided to his biographer, Bertram D. Wolfe, particularly of his skirmishes with Soviet bureaucrats, artists, and art theorists.

But a man’s life is his own, and his summation of it is his own, too. As I go over this book for the last time in manuscript, I think that it is one of the frankest confessions I have ever read. If Rivera now spares the Soviets, he does not spare himself; he certainly does not spare his enemies. And the breadth of his sympathies, the vitality and love for life which runs through his prose as it does through his paintings—who can allow these qualities to a mere factional man?

Essentially, then, this is Rivera’s apologia: a self-portrait of a complex and controversial personality, and a key to the work of perhaps the greatest artist the Americas have yet produced.

As I was preparing the final pages of manuscript, I received the news that Diego Rivera had died on November 25, 1957, in his home in San Angel.

In contrast with so much of his life, marked by the furor of partisan controversy, his death came peacefully.

Up until several weeks before the end, Rivera had been at work, painting with the vigor which had characterized his work for more than half a century. An attack of phlebitis paralyzed his right arm and he was put to bed. A heart specialist, a friend of the family, observed a steady deterioration in his condition.

At 11:30 on the night of November 25th, he rang the bell beside his adjustable hospital-type bed.

His wife, Emma Hurtado, came into the room. “Shall I raise the bed?” she asked.

He replied, “On the contrary, please lower it.”

These were his last words.

Dressed in a blue suit and tie and a red shirt, and sheathed in a casket of brown steel, the remains of Diego Rivera were lowered into the earth of the Rotunda of Mexico’s Illustrious Sons, Dolores Cemetery. In the same hallowed ground lie the bones of Benito Juárez, Mexico’s greatest hero.

GEOGRAPHICAL, GENEALOGICAL

THE MOUNTAINS OF GUANAJUATO rise seven thousand feet into the clear Mexican air. At their base is a bowl-shaped hollow which, even a small way up the slopes, appears to be strewn with tiles of many colors. The mountains are rugged and lowering, but they hold rich veins of silver. In the year 1550, a mule driver named Juan Rayas discovered the first of Guanajuato’s silver mines. Four years later a group of Spaniards settled in a curve of the bowl and thus founded the town. From that time to this, the people of Guanajuato have taken silver from the rocks.

The town is in central Mexico; its houses are flat-roofed, the windows are shadowed and deep, and there is a somnolent air about the afternoons. Even in my childhood the silver-rush days were already only a memory, for most of the veins near the surface of the ground had been emptied. It was other places in Mexico that were luring the fortune hunters and adventurers.

The house of my parents, Diego and Maria Barrientos Rivera, was located at 80 Pocitos Street, in the heart of Guanajuato. It was like a small marble palace in which the queen, my mother, was also diminutive, almost childlike, with large innocent eyes—but adult in her extreme nervousness.

There was mixed blood on both sides of my family. My maternal grandmother, Nemesis Rodríguez Valpuesta, was of an Indian and Spanish mixture. The family of my maternal grandfather, Juan Barrientos, a mine operator, had come from the port of Alvarado, celebrated all over Mexico for its excellent fish, its opulent fruit, and the gaiety and vigor of its Negroid people. It is not unreasonable, therefore, to suppose that my mother passed on to me the traits of three races: white, red, and black.

My father’s mother, Grandmother Ynez Acosta, was descended from a Portuguese-Jewish family which traced its ancestry to the rationalist philosopher Uriel Acosta. At fifteen she had married my paternal grandfather, Don Anastasio de Rivera. Don Anastasio was then sixty, a veteran officer of the Spanish army, and the son of an Italian who had also served as an officer in the military forces of Spain. While still in the Spanish army, my paternal great-grandfather had been sent on a diplomatic mission to Russia at the end of the eighteenth century. There my grandfather had been born. No one in Spain knew who my grandfather’s mother had been. As my grandfather told my father, many could present themselves as the son of an unknown father, but only he, Don Anastasio, enjoyed the distinction of being the son of an unknown mother. The explanation was that my Italian great-grandfather had married in Russia, his wife died in childbirth, and he brought his son back with him to Spain. It was through Don Anastasio that I could claim the title to Spanish nobility which I afterwards transferred to a relative.

Don Anastasio did not marry till after he had come to Mexico, and at an age when most men are considered old. He was, however, a man of fabulous vigor. At sixty-five he joined Juárez in the war against the French and the Church. When he settled down again, he quickly amassed a large fortune. To his wife, he presented a brood of nine children. He was seventy-two when a twenty-year-old girl, jealous of the attention he still bestowed on my grandmother, gave him poison to drink, and so he died.

Through the long years that followed, in which my Grandmother Ynez raised and supported her children, she never forgot my grandfather, Don Anastasio, with whom she continued to be madly in love. She would tell us that no young man of twenty could have served her as a lover better than he had.

Hearing this over and over again from my grandmother, my naturally fearful mother came to suspect that my father had inherited this terrible virility. And not without reason. My father was a powerfully built man, tall, black-bearded, handsome, and charming. He was fifteen years her senior, but in speaking of his age, my mother would give him additional years in the hope of making him seem less attractive to other women.

TALE OF A GOAT AND A MOUSE

To THESE PARENTS, a twin brother and I were born on the night of December 8, 1886. I, the older, was named Diego after my father, and my brother, arriving a few minutes later, was named Carlos. My whole name actually is Diego Maria de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez.

The coming of Carlos and me brought great joy to my parents. At twenty-two, my mother had already had four pregnancies, of which the first three had ended in stillbirths. After each child was born dead, my father had gone out and bought my mother a doll to console her. Now he did not buy a doll but cried with delight.

However, when he was only a year and a half, my twin brother Carlos died. My mother developed a terrible neurosis, installed herself beside his tomb, and refused to leave. My father, then a municipal councillor, was obliged to rent a room in the home of the caretaker of the cemetery in order to be with her at night. The doctor warned my father that, unless my mother’s mind was distracted by some kind of work, she would become a lunatic.

The family explained her case to my mother and urged her to study for a career. She agreed, chose obstetrics, and began her studies at once. To everyone’s delight, the cure succeeded. My mother’s melancholia passed. In school, she proved to be a brilliant student and received her diploma in half the regular time.

At two years old, according to photographs and the tales of my father and mother, I was thin and had rickets. My health was so poor that the doctor advised that I be sent to the country to live a healthy, outdoor life, lest I die like my brother.

For this reason, my father gave me to Antonia, my Indian nurse. Antonia, whom I have since loved more than my own mother, took me to live with her in the mountains of Sierra.

I can still recall Antonia vividly. A tall, quiet woman in her middle twenties, she had wonderful shoulders, and walked with elegant erectness on magnificently sculptured legs, her head held high as if balancing a load. Visually she was an artist’s ideal of the classic Indian woman, a

nd I have painted her many times from memory in her long red robe and blue shawl.

Antonia’s house was a primitive shack in the middle of a wood. Here she practiced medicine with herbs and magic rites, for she was something of a witch doctor. She gave me complete freedom to roam in the forest. For my nourishment, she bought me a female goat, big, clean, and beautiful, so that I would have milk fresh from its udders.

From sunrise to sunset, I was in the forest, sometimes far from the house, with my goat who watched me as a mother does a child. All the animals in the forest became my friends, even dangerous and poisonous ones. Thanks to my goat-mother and my Indian nurse, I have always enjoyed the trust of animals—precious gift. I still love animals infinitely more than human beings.

I had left my home for Antonia’s when I was two years old, and I returned when I was four. Now I was no longer scrawny, but robust and fat. But my body was out of proportion in two respects: my feet were too small for my legs, and my forehead was too high and wide for my face. However, my two years with Antonia had saved me from any early deformation of the mind; until then I had been growing up as the animals, free from human dirt. Many years later, I wondered whether my father had not planned it so, that I might escape the prejudices and lies of adults.

Not long after my return from the mountains, I had my first encounter with adult duplicity. I was five. My mother was pregnant, and she wanted to fool me about the approaching birth. She told me the child would be delivered to her in a box which the train was carrying from afar. That day I waited at the depot and watched all the trains, but no box arrived for my mother. I was furious when I returned home and found that my sister Maria had been born during my absence.

In angry frustration, I caught a pregnant mouse and opened her belly with a pair of scissors. I wanted to see whether there were small mice inside her. When I found the mouse foetuses, I stomped into my mother’s room and threw them directly in her face, screaming, “You liar—liar.” My mother became hysterical. She cried out that in giving birth to me she had whelped a monster. My father also scolded me. He told me of the pain I had caused the mouse in cutting her up alive. He asked if my curiosity was so strong that I could be indifferent to the sufferings of other creatures. To this day, I can recall the intensity of my reaction. I felt low, unworthy, cruel, as if I were dominated by an invisible evil force. My father even started to console me.

My Art, My Life

My Art, My Life